This passage reflects King Ludwig II’s deep personal connection to the construction of Neuschwanstein Castle and his romantic vision for it. It details his desire to recreate the grandeur of old German knights’ castles and hints at his retreat into a world of myth and legend, as evidenced by his references to “Tannhäuser” and “Lohengrin.” Ludwig envisaged the castle not only as a personal refuge but as a sanctuary for honored guests and a tribute to the composers and legends that inspired him.

The political undertones of the castle’s construction are not overt in this passage, but they are an essential part of its history. Following Bavaria’s defeat and forced alliance with Prussia, Ludwig found himself stripped of genuine sovereign power, particularly over his military, which he deemed the greatest tragedy of his life. Neuschwanstein became a project of defiance and self-expression, a place where Ludwig could immerse himself in an idealized kingdom of his own design, reflecting his yearning for a bygone era of absolute monarchy and his role as a patron of the arts.

This personal kingdom took shape in the form of his various castles and palaces, with Neuschwanstein being the most famous, symbolizing his resistance to the political changes of his time and his retreat into a romanticized past.

“More beautiful and habitable than the lower castle of Hohenschwangau”

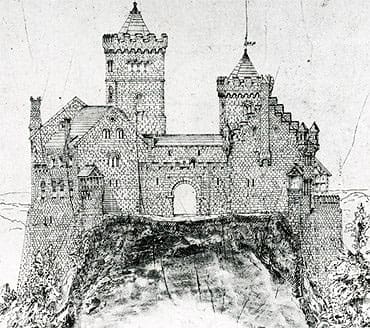

The influence of Crown Prince Maximilian II of Bavaria, the father of Ludwig II, was pivotal in shaping the young king’s romantic inclinations. Maximilian’s restoration of the Schwanstein Castle ruins in the Gothic style from 1832 laid the groundwork for Ludwig’s fascination with medieval themes. The castle, set amidst the enchanting mountain landscape, became a cherished retreat for Ludwig, who spent much of his youth there.

Hohenschwangau was adorned with tapestries and paintings that depicted medieval legends and poetic tales, notably the legend of the Swan Knight, Lohengrin. Ludwig, even in his youth, felt a profound connection to the character of Lohengrin, which was later immortalized in Richard Wagner’s opera created in 1850. This personal identification with the Swan Knight was more than symbolic; it was an alignment with the legacy of his own family, as the swan was the emblem of the Counts of Schwangau, from whom Ludwig was descended.

King Maximilian II had embraced the swan as a recurring theme throughout Hohenschwangau, effectively weaving the family’s heritage with the idealized vision of the Middle Ages. In this way, Ludwig’s later projects, including the construction of Neuschwanstein Castle, were not only a tribute to his passion for Wagner’s music and the chivalric age but also a continuation of his father’s efforts to blend medieval romanticism with the family’s lineage and local Bavarian culture.

“The location is one of the most beautiful to be found”

Maximilian II, with a deep appreciation for the natural beauty surrounding Hohenschwangau, had trails and vistas created to fully enjoy the landscapes.

In the 1840s, as a birthday tribute to his consort Marie, an avid mountain enthusiast, he commissioned the construction of “Marienbrücke”, a bridge perched above the Pöllat Gorge.

The “Jugend”, a slim mountain crest to the left of the Pöllat, offered spectacular views of the surrounding mountains and lakes, a spot dearly favored by Maximilian II. He even had plans for a viewing pavilion on this ridge in 1855. Crown Prince Ludwig, the future King Ludwig II, was known to frequent the “Jugend”, no doubt inspired by the panoramic splendor of the site.

“In the authentic style of the old German knights’ castles”

Atop the “Jugend” stood the remnants of the small fortresses Vorder- and Hinterhohenschwangau. It was upon this historical foundation that Ludwig II envisioned the construction of his “New Hohenschwangau Castle” — a name that would only be changed to “Neuschwanstein” following the king’s demise. His ambition was to erect a fortress that surpassed the medieval authenticity of Hohenschwangau, marrying historical accuracy with contemporary technological advancements.

In 1867, Ludwig II’s visit to the recently restored Wartburg Castle further fueled his creative vision. He was particularly taken by the Singers’ Hall, celebrated as the venue for the mythical “Singers’ Contest.” The Wartburg, along with its hall, thus became a central inspiration for Ludwig’s new project. Architect Eduard Riedel was tasked with integrating these concepts, along with the theatrical set designs of Christian Jank, a Munich scene painter, into the castle’s final blueprint.

“Looking forward to living there one day (in three years)”

The construction of the castle did not progress as swiftly as King Ludwig II had hoped. The scope of the project was vast, and the mountainous location posed significant challenges. A team of set designers, architects, and craftsmen worked tirelessly to bring the king’s intricate visions to life. The aggressive timelines he demanded were often met only by laboring around the clock.

The cornerstone of the “New Castle” was laid on September 5, 1869. The first structure to be completed was the Gateway Building, within which Ludwig II took up residence for several years. It was not until 1880 that the Palas, or main building, held its topping-out ceremony, and the king was able to move in four years later, in 1884.

As King Ludwig II became more reclusive and immersed himself in his regal persona, he altered the initial plans for the castle. The designated guest rooms were scrapped in favor of a “Moorish Hall” adorned with a fountain, though this room was never realized. The initial “Writing Room” underwent transformation into a small grotto from 1880 onwards.

The originally modest “Audience Room” evolved into a grand Throne Room, not intended for holding audiences but rather as a symbolic tribute to monarchy, emulating the fabled Grail Hall. Integrating this majestic hall into the already standing structure of the Palas necessitated advanced steel construction techniques.

In the west wing of the Palas, plans included a “knights’ bath,” echoing the ceremonial baths of the knights of the Holy Grail. Presently, this area houses a staircase for visitors, providing a route down to the castle’s exit.